organised by the Innovative Business Centre in cooperation with the Energy Watch Group at the European Energy Security Forum 2014

26 September 2014

Session 1

SPEECH BY MEP BENEDEK JÁVOR

We have seen that several support mechanisms and forward looking initiatives exist in the diverse fields of renewable energy, yet, there are still substantial obstacles and barriers for further development of renewables both in financial terms and attitudes.

In my short presentation I look at some of the challenges and give a few examples to show the need for re-contextualization of the renewable energy agenda and making clear links with various issues like energy efficiency, energy security, environment, climate change mitigation, not to forget energy poverty and wellbeing.

I point to some of the interlinkages, highlight possible synergies and call for establishing or reinforcing the policy links among these issues. The geographical scope of the paper is mainly Europe with an outlook to regional (Eastern-Central Europe) or country level aspects.

The EU has committed itself to a low carbon economy, which implies a much greater need for renewable sources of energy. The use renewables is also crucial for reducing the EU’s dependence on energy imports (EU dependency increased from less than 40 % of gross energy consumption in the 1980s to reach 53.4 % by 2012), and its vulnerability to price increases. According to the Commission estimates, by moving towards a low carbon economy EU could save € 175-320 billion annually in fuel costs over the next 40 years.

However, we all see that the current energy and climate framework with 3 interlinked targets on energy efficiency, greenhouse gas reduction and renewable energy) is at risk of being consolidated into a single emission reduction target. This would likely result in an uncertain future for the EU’s renewables sector and other low-carbon technologies. These projects in general face a danger of cost overruns, operational and regulatory risks, problems of carbon price and weather variability, public acceptance. Renewables are associated with very significant investment needs and long payback times. Besides, these projects have the added risk of uncertain load factor due to grid integration challenges. Hence, spreading renewables is highly challenging from a policy point of view.

Focus of my speech is on a coherent policy framework and appropriate financing.

I argue that the foreseen reform of climate and energy policy in itself would not provide sufficient motivation to all member states, business, households and other actors for a wide-scale sustainable energy use.

To give you 2 examples from my country, according to a recent study, 75 – 85% of households in Hungary do not have any savings; 80% of those households planning energy related investments would not take a bank loan to cover the investment costs.

If we look at the allocation of renewables-related development funds in the country, mayor distortions occur, as well.

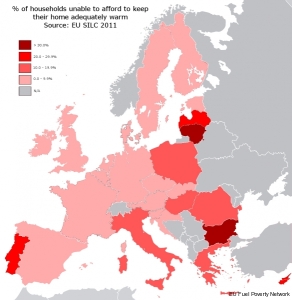

The link between renewables, climate change mitigation and energy efficiency is obvious. There are other, seemingly unrelated aspects, too. Here I would like to highlight the importance of combining green energy efforts with the alleviation of energy poverty. To put it simply, energy (or fuel) poverty occurs when a household is unable to heat its home or afford to use energy services at an adequate level which hampers the fulfillment of other basic needs of individuals. Based on estimates from EPEE (European fuel poverty and energy efficiency) project, 50-125 million EU citizens are affected.

As the map below shows, a main aspect of energy poverty is manifest across the EU.

% of households unable to afford to keep their home adequately warm

Source: EU Fuel Poverty Network

To flag some of the multiple consequences of energy poverty: across the EU as a whole, 9.8% of the population are unable to keep their home adequately warm, 15.5% live in homes that are damp, rotting or leaking, and 8.9% are behind on payments for utility bills (results of recent Fuel Poverty research based on 2011 data from the Eurostat SILC survey). In addition, energy poverty is associated with a wide range of physical and mental illnesses. According to a recent study, only in Hungary, 5000 deaths per year can be associated with non-adequately heated homes.

If we take a closer look at the characteristics of energy poor households (regardless of the exact definition or threshold) we can see that – besides other features – these households usually inhabit buildings with bad energetic characteristics (including panel blocks in Eastern-Central Europe).

If we look at former energy poverty alleviation strategies across Europe based on income or energy prices (subsidies, tariff policies) have often turned out to be contraproductive and become a burden for public budgets.

It is only when synergies between building efficiency, social welfare and climate mitigation was recognised that the policy efforts have accelerated in parts of Europe (e.g. Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, energy-efficient refurbishments). Studies focusing on Eastern Central Europe show that efficiency improvements and sustainable energy investments would enable many households to escape energy poverty, yet due to their unfavourable financial situation households cannot take the necessary investments and thus this potential synergy remains unexploited in the region.

Another striking example is that while in many countries households are incentivised to use sustainable energy, in my country, the payment of the utility bills are subsidised – mostly providing a driver for higher consumption of imported gas instead of shaping attitude towards energy savings, improved efficiency and greener sources.

This brings me to the issue of financing low carbon investments.

Renewable energy investments, according to recent data from Hungary, are mainly concentrated to upper middle class living environments, as they need a remarkable contribution from the households themselves. This characteristic cuts off low income households from being beneficiaries of renewable subsidies, as well as from harvesting the energy and cost advantages of such investments. Very simply we can say, that most of the public money spent on household energy efficiency and small-scale renewable investments is finally allocated to, and supports middle or high income households, and thus these subsidies are widening the gap between low and high income groups.

The presentation does not allow me to address the issue in its complexity, yet I see an opportunity for vulnerably groups in mainstreaming the ESCO (Energy Service Company) financial model. An other important issue is creating specialized programmes for low income households, marginalized groups – like the Roma community in Central and Eastern Europe, or immigration groups in the West – and financially extremely fluctuating and vulnerable families. In this environment very often the simple electrification of the buildings is not established yet, so cheap, affordable and low tech renewable solutions might move those households from the 19th to the 21st century.

In my presentation I argued that separate energy policy goals might not lead to wished results. There is a need to show co-benefits of renewables in terms of social and economic aspects. I used energy poverty as an example show that linking different policy goals is likely to tip the cost-benefit balance and help mobilise efforts of the stakeholders in all fields.

As for renewables, possible directions, steps include:

- developing a common understanding of related concepts, indicators

- further improving relevant research and establish a proper science-policy interface

- developing methodologies to quantify co-benefits and co-costs

- establishing specified, well targeted programmes for disseminating the benefits of energy efficiency and renewable investments for our most needy fellow citizens .

On that basis, further and better targeted incentives can be drawn for the wider use of renewables, which not only help boosting the economy and improving employment in the EU, but also brings about substantial benefits for the environment and the whole society.

To conclude, I argue that the new climate and energy policy has to be comprehensive combining renewable energy target with further aspects in order to bring a socially just transition.

LINKS, REFERENCES:

http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2013/pdf/ocp145_en.pdf

http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/towards-a-green-economy-in-europe

http://energiaklub.hu/sites/default/files/energiaklub_poverty_or_fuel_poverty.pdf

http://fuelpoverty.eu/wp-content/gallery/fuel-poverty-maps/eu-inability-to-heat-home-map-031013.jpg

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421511009918