The aftermath of the Ukrainian crisis, the Russian military intervention and the undeclared war in eastern Ukraine brought about a crucial change in the EU’s foreign affairs. The new understanding of a conflict-oriented and imperial rationality-based attitude of the Russian leadership caused a substantial shift in the EU’s Russia-politics – and raises security questions not only at European level but also on the global scale.

The military conflict in Ukraine has brought to the forefront the issue of energy security and the need to reduce all forms of energy dependency from Russia. Underlining this is importance of the EU speaking with one voice in energy policy as well as in its foreign policy.

Russia is the EU’s biggest neighbour and its third biggest trading partner. In the last decade, EU-Russia relations have been characterised by mutual recognition and increasing cooperation, which was evident not only in the fields of trade and economic cooperation. The so-called common spaces cover aspects such as research, culture, education, environment, freedom and justice. Moreover, negotiations have been ongoing since 2008 to further strengthen the partnership and have legally binding commitments in all areas including political dialogue, freedom, security and justice, research, culture, investment and energy. After 2010, the partnership for modernisation has become the focal point for cooperation, reinforcing dialogue initiated in the context of the common spaces.

Not acceptable in any sense

The role of Russia in the Ukrainian crisis shed light on the fact that Russia is not on track in the process of democratisation and modernisation in the way the EU had believed. Russian politics did not become more moderate through the cooperation with the EU, but rather the opposite occurred. Even if we accept the experts’ argumentation for the need for a ‘buffer zone’ between the EU and Russia, the illegal annexation of Crimea and the continuous destabilisation of Eastern Ukraine including aggression by Russian armed forces on Ukrainian soil cannot be considered acceptable in any sense. These issues give a clear indication of the unchanged aggressive nature of Russian politics and leadership. It became clear that Putin is primarily led by imperial rationality and now it seems that Putin’s Russia is no longer interested in a trustworthy and functional relationship with the EU.

Since 2014, the EU has progressively imposed restrictive measures in response to the annexation of Crimea and the destabilisation of Ukraine. After a series of rocket attacks in Mariupol by pro-Russian separatists in January this year, the Latvian EU presidency has called on a council of EU foreign ministers to prepare the ground for a summit of EU leaders on the crisis with Russia and to determine the role the EU should take. The developments over the past two years call for a new interpretation of the Russian-EU relationship as they demonstrate that Putin’s Russia is impossible to handle with peaceful approaches and methods based on seeking consensus. It is all the more important that the EU speaks with one voice and acts in a united manner. And this is exactly what is missing.

A need for clear signals

Some EU member states including Poland and the Baltic states regularly use strong anti-Russian rhetoric, while others, such as Hungary, take political decisions showing an opening towards Russia. These seemingly contradictory attitudes, however, might stem from a common fear of growing Russian influence – partly due to historical reasons. The only difference lies in the role these national governments attribute to the EU (or the US) in handling the conflict, depending on the extent they believe that the EU is willing and able to send clear signals to Russia.

Germany itself, having a huge influence on EU politics, has recently re-evaluated the Russian relationship. Before, Germany had the standpoint that a close economic cooperation could have a stabilising effect on Russia and reduce the possibility of aggressive geopolitical measures. They hoped that this cooperation might also further the modernisation of the Russian economy and thus it might contribute to the creation of a Russian state that was linked to the world economy not only through its energy export, but with many other ties and which has its interests in sustaining the balance of international relationships. Germany, however, has realised that these presuppositions and hopes were wrong. Therefore, Chancellor Merkel placed harsh measures and defends consistently the sanctions that the EU adopted in response to Russia’s military intervention in the Ukraine.

The sanctions in place include the suspension of most cooperation programmes, suspended talks on visas and the new EU-Russia agreement, as well as restrictive measures targeting sectorial cooperation in the fields of defence and sensitive technologies, including those in the energy sector. Russian access to capital markets is also restricted. The European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development have suspended the signing of new financing operations in Russia and a trade and investment ban is in force for the Crimea region.

The sanctions would have expired in the course of this year, yet various EU leaders stressed that the EU should maintain the sanctions until Russia stopped the aggression in Ukraine. Thus, the Council meeting of June 2015 extended the restrictive measures and economic sanctions until June 2016. These sanctions, however, are somewhat questionable in their effect.

Thus, the EU has to find a way to ensure aid and protection for the civilian population in eastern Ukraine as well as to find a new balance in the EU-Russian relations. In this respect, again, speaking with one voice is essential. Finding a new balance is key in the broader context, for the sake of a global equilibrium as well, as Russia might opt for building stronger links to China.

Extreme dependency

These recent developments also affect the issue of energy security in the EU, which is very high on the political agenda now. However, the impacts of Russia’s nuclear investments in the EU are not seriously considered.

We are all aware that the EU is extremely dependent on external energy sources, mainly coming from Russia. (And vice versa, supplies of oil and gas make up a large proportion of Russia’s exports to Europe, which are crucial for the Russian economy. The recent collapse of the Russian economy due to the rapid fall of oil prices is a clear proof of this, as it has shown that the country’s self-confidence merely stemmed from high oil prices.)

The dependency on Russian fossil fuels and the lack of diversification of energy sources have been widely recognised in the EU’s energy policy. However, these are only a small part of the whole picture. The impacts of Russia’s fossil or nuclear investments in the EU are hardly considered in the energy-related acquis, even though it is obvious that through its energy corporations, the Russian government has means of influence far beyond the mere business transactions.

Energy dependency can appear in multiple forms including financial, technological or fuel dependence in the nuclear and fossil sectors, acquisition and ownership of strategic energy infrastructure as well as investments in energy projects by Russia in the EU, in particular, the Baltic and the Central-Eastern European member states. Here again, we see no unified behaviour from EU member states. Some EU member states have reconsidered their cooperation with Russia, or Rosatom in particular, as a consequence of the crisis in Ukraine. For example: Germany refusing to sell gas storage capacities to Russia; Bulgaria refusing a second Rosatom nuclear plant; Slovakia stopping negotiations with the Russian nuclear complex; and the UK suspending its negotiations with the company. At the same time, some EU countries such as Finland or Hungary still consider building new nuclear power plants partly using Russian financial sources, technology, fuel and waste management facilities. It is the responsibility of the EU bodies to ensure that decisions in any member state do not undermine the energy security of the EU as a whole.

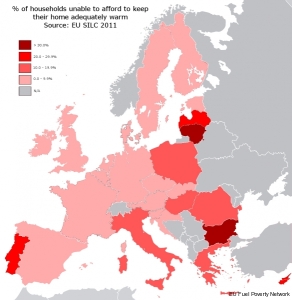

Equally importantly, the EU should think out of the box and look beyond resource route diversification and new infrastructure projects, when it comes to improving energy security. A systemic, long term solution for the problem is increased energy efficiency with special attention to the transport sector, residential buildings and industrial sites and the wide-scale use of local, renewable energy sources building upon, inter alia, novel financial solutions and community-based models. Energy efficiency and renewables projects could be very useful components of this project, as they could contribute to reducing all forms of energy dependencies.

To conclude: even if the hopes of the EU for the stabilisation and democratization of Russia have failed to come true, geopolitical realities are given. The EU has to reassess its relationship with Russia, to act firmly in a united manner and to tackle security threats at all levels, including in the field of energy policy. The EU should work for a healthier relationship with Russia in this regard, as well, by systemically reducing its dependency, wherever possible – yet acknowledging long-term mutual dependencies which can be used as a basis for the new balance.

(An earlier version of this article was published on the website of the Green European Journal in February 2015.)